About Raymond

Raymond Merrill Smullyan (1919–2017) was an extraordinary creative personality: mathematician, philosopher, Taoist, magician, pianist, and author of some thirty books on various topics which continue to have a worldwide audience in many languages. With Martin Gardner, he is considered one of the fathers of recreational mathematics. To the many who knew him, he was also a beloved friend whose good nature and wisely free-spirited view of life were contagious, liberating and uplifting.

Raymond was born in Far Rockaway, New York on May 25, 1919 to Rosina Freeman Smullyan and Isidore Smullyan, who had arrived in America about 12 years earlier.

Raymond was the third of three talented children; his ten-years-older brother Emile (later known as Emile Benoit) became an economist and diplomat, and his five-years-older sister Gladys (later known as Gladys Gwynne) was for a time an actress in Hollywood.

Raymond was also particularly close to his cousins Arthur (in later life also a philosopher and logician) and Robert (a painter), as they were double cousins: as if to foreshadow the improbable complications of some of his logical riddles, their mother was Raymond’s mother’s sister, and their father, Raymond’s father’s brother.

At the time of Raymond’s arrival, the family was enjoying the peak of success as his father served as the president of a company involved in importing specialty steel products from Europe.

Raymond loved each of the houses his parents were living in, the second one in particular. Although his instrument would later be the piano, he is pictured here serenading his dog Lucky with a violin at the second home, the Kubie Estate.

The tenor of his family life in those days is captured in an oft-told tale about an encounter with his older brother on April Fool’s Day.

The classic retelling came in Raymond’s book What Is The Name Of This Book? (1978):

My introduction to logic was at the age of six. It happened this way: On April 1, 1925, I was sick in bed with grippe, or flu, or something. In the morning my brother Emile … came into my bedroom and said: “Well, Raymond, today is April Fool’s Day, and I will fool you as you have never been fooled before!” I waited all day long for him to fool me, but he didn’t. Late that night, my mother asked me, “Why don’t you go to sleep?” I replied, “I’m waiting for Emile to fool me.” My mother turned to Emile and said,” Emile, will you please fool the child?” Emile then turned to me, and the following dialogue ensued:

Emile / So, you expected me to fool you, didn’t you?

Raymond / Yes.

Emile / But I didn’t, did I?

Raymond / No.

Emile / But you expected me to, didn’t you?

Raymond / Yes.

Emile / So I fooled you, didn’t I?

Well, I recall lying in bed long after the lights were turned out wondering whether or not I had really been fooled.

Unfortunately, the Great Depression and the destruction wrought by a flood on his father’s business premises, brought hard times, and the family moved to Manhattan and never regained the level of comfort they had earlier enjoyed. Raymond regretted the loss of the Far Rockaway years for the rest of his life.

Raymond did not go to school in Manhattan, because the likely ones there were boys’ schools, but instead, impelled by an interest in the opposite sex that never left him, he opted to attend a coeducational school, Theodore Roosevelt High School, in the Bronx.

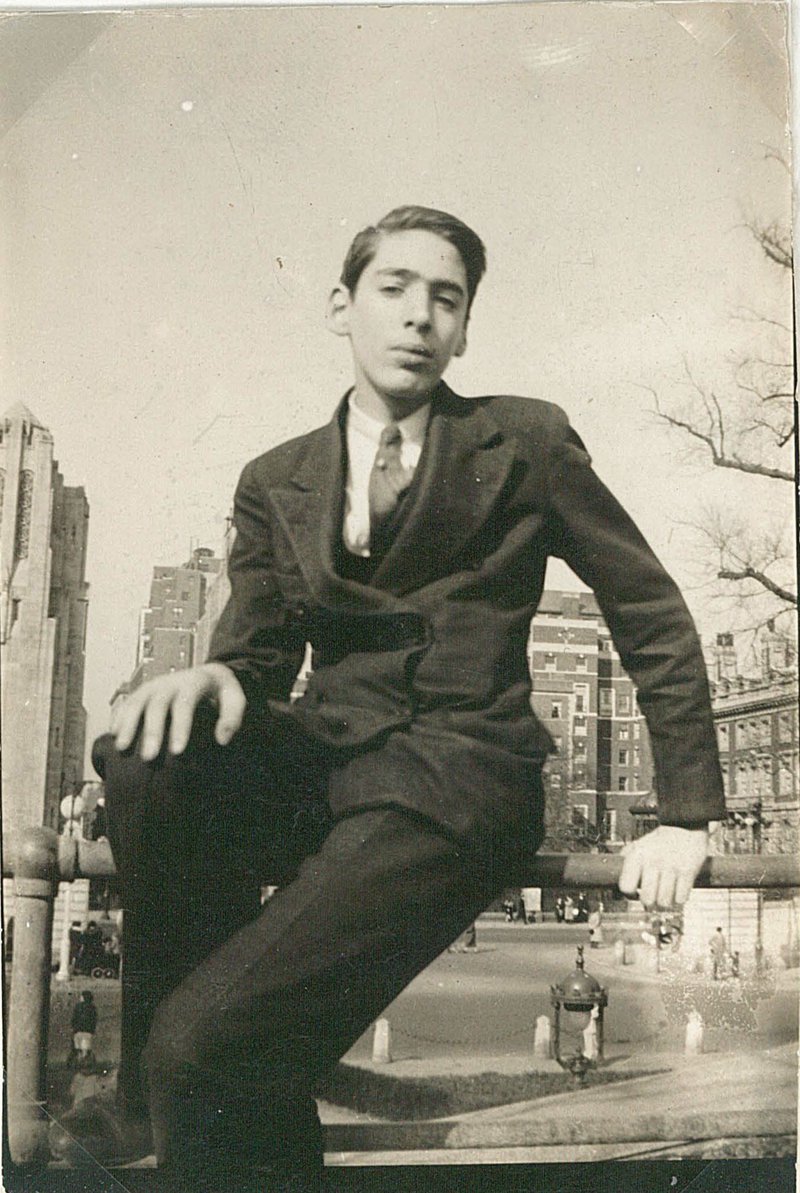

Then he began a pattern of dazzling teachers with mathematical and musical brilliance without obtaining the credentials the school offered. He dropped out of high school while simultaneously auditing courses at Columbia. (It’s believed this photo shows him there at this time.)

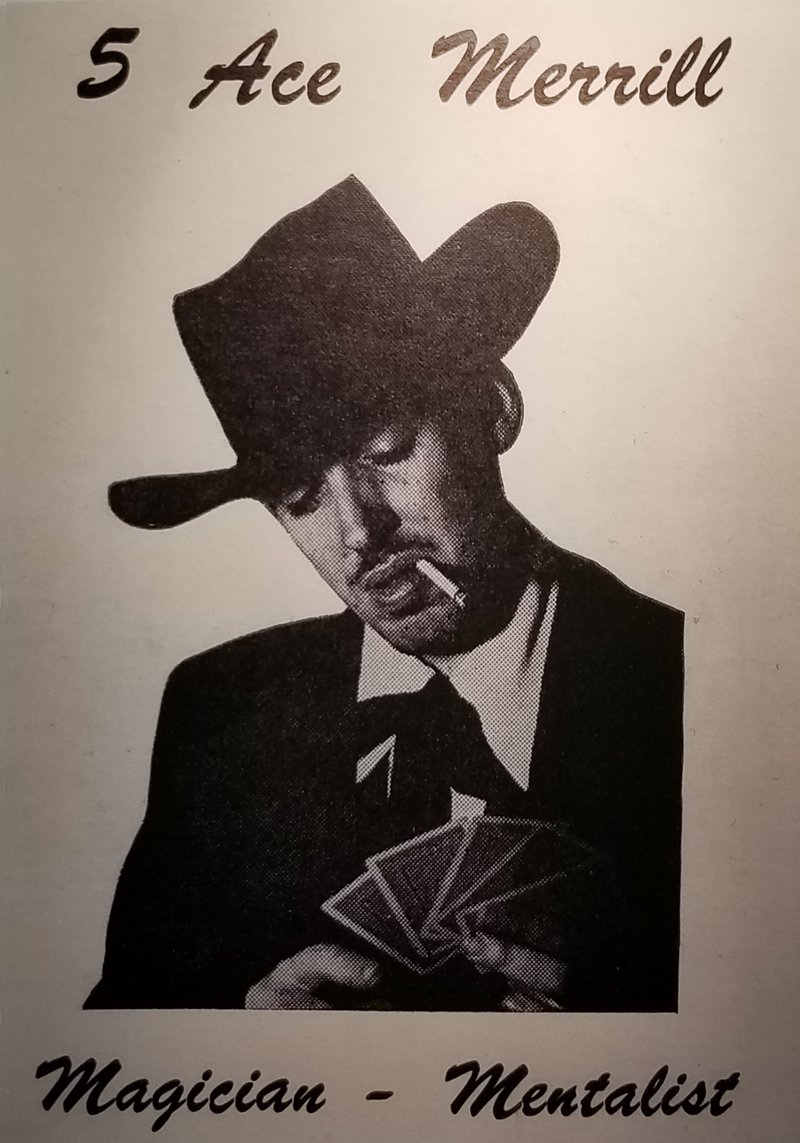

He subsequently studied for short periods of time, all without the benefit of a high school diploma and all without obtaining a bachelor’s degree either, at a variety of prestigious colleges and universities. After a time, he took a break and earned a living as a magician at the Pump Room in Chicago, under the stage names of Raymond Merrill and Five-Ace Merrill.

Shortly thereafter, he was hired to teach mathematics at Dartmouth College, which he did, still without a university degree. The bachelor’s degree he lacked eventually came in 1955 from the University of Chicago, partly based on credit he received for a course he had taught at Dartmouth.

Throughout these years of wandering, he circulated a number of seminal papers in the field of formal logic, never straying too far from notions of self-reference and Gödelian theory. He then entered the graduate Mathematics program at Princeton, which awarded him a Ph.D. in 1959, under the supervision of Alonzo Church, the noted mathematician and pioneer of computer science. Other mentors of Smullyan at this stage included Rudolf Carnap, Willard Van Orman Quine and John Kemeny.

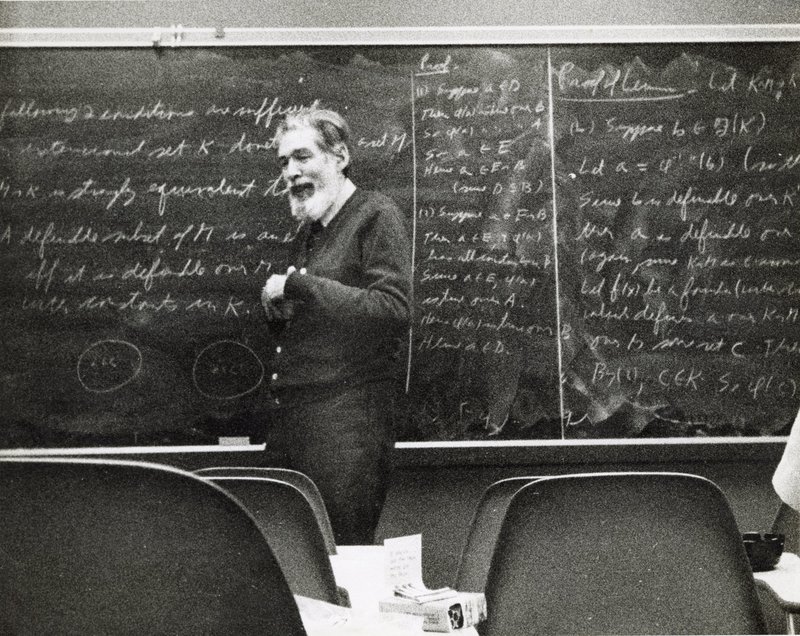

From this stage onward until his retirement, he published widely in the field of formal logic, taught mathematics and philosophy, holding teaching appointments and/or professorships at Princeton University, Yeshiva University, Lehman College, City University of New York, and most especially Indiana University in Bloomington, where for many years he was Oscar Ewing Professor of Philosophy. He published prolifically in mathematics journals such as the Journal of Symbolic Logic and the Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, and continued to do so up through retirement.

From the 1960s on, his personal home base was a small house on several acres of woodland in the vicinity of Tannersville, NY in the Catskills. This structure, purpose-built to afford panoramic views, situated next to his brother’s cottage, became the place he felt happiest.

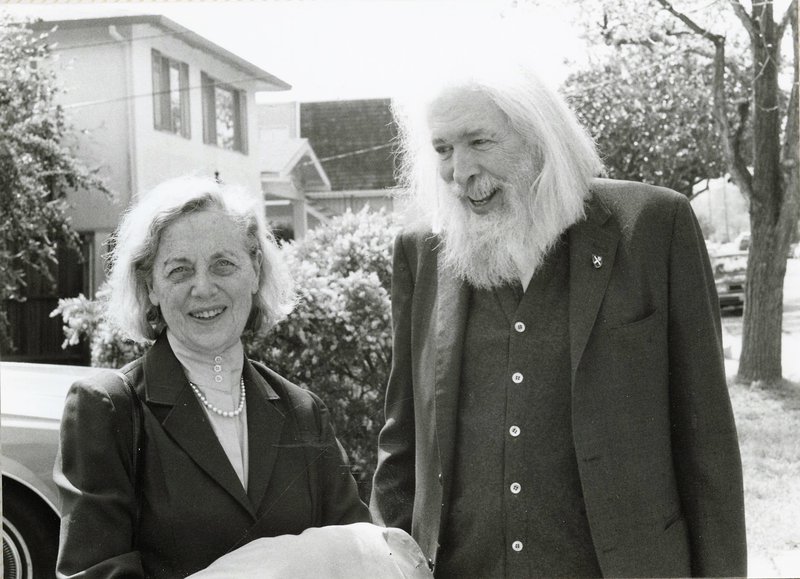

During their time there, he and his wife Blanche (whom he married in 1960) entertained a continuing parade of his teachers, students, admirers and family members.

(Not to mention family dogs, to whom he would explain that it was better to be a good dog than a bad dog.)

Books and recorded music filled every nook and cranny, along with devices associated with various of his passions, including music reproduction, stereoscopic photography, and astronomy. Dominating two rooms in the house were grand pianos.

Starting in 1977, Raymond began writing the books for which he is best known to the public.

The first published was philosophical, The Tao Is Silent (1977). [A couple of representative covers] Many were logical puzzle books in which, through chains of related brain-teasers, Raymond would make it possible for readers lacking training in the language and the substance of formal logic to grasp some of the problems he was tackling professionally. These included What Is the Name of This Book?(1978), Alice in Puzzle-Land (1982) and The Lady or the Tiger? (1982). Though many of these books are, by the end, fearsomely demanding of the reader’s logical acumen, they reach those dizzy heights by easy steps and with tremendous charm, and won him a global following as his books were translated into many languages. He even appeared on the Johnny Carson show in 1982.

Raymond also wrote two books of chess problems of a distinctive type (“retrograde analysis” problems, in which you are shown an often bizarre chess position and need to deduce how it was arrived at) :The Chess Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes (1979) and The Chess Mysteries of the Arabian Nights (1981). Other books were devoted in whole or part to memoir, like Some Interesting Memories: A Paradoxical Life (2002) and Reflections (2015). There was even a 2009 anthology of accounts of the lives and interests of members of The Piano Society, with which he was affiliated: In Their Own Words: Pianists of the Piano Society.

In addition to popular books, he wrote nine technical books, starting with Theory of Formal Systems (1961) and First-Order Logic (1968) and ending, remarkably, with three textbooks on mathematical logic written in his ninth decade: Logical Labyrinths (2009), A Beginner’s Introduction to Mathematical Logic (2014) and A Beginner’s Further Introduction to Mathematical Logic (2016).

He sometimes called himself a “mathemugician,” which leaves out many of his endeavors but gives some sense of them. In his last years, he would drive or be driven to local restaurants almost every evening, and wander around the dining room with a pack of cards and a mischievous gleam in his eye, searching out children and attractive women to amaze with a magic trick or two, frequently accepting payment from the latter in the form of kisses.

In his latter years, he seemed to refocus much of his attention on the piano, making recordings of some compositions he loved best and consorting with musicians who like him resided on the mountainside, augmented by the virtual international company of The Piano Society. But he continued to lecture at universities and conferences throughout his eighties and nineties, and in the last seventeen years of his life wrote and published, astoundingly, fifteen books. His books of puzzles enjoyed a resurgence of popularity beginning in 2008 due to the reprints of his work by Dover Publications. His audience of readers and admirers expanded to include new generations of high-school and college students, who considered him a a "rock star."

Raymond’s wife Blanche died at age 100 in 2005, but Raymond carried on bravely and positively by continuing to write, socialize with old and many new friends, and frequent his favorite mountain eateries to entertain visitors with magic and an astonishingly wide repertoire of jokes, both erudite and corny. In his last year his health suffered; he declined in hospital, and to return home required the help of a nurse. At the ripe age of 97, his lungs finally gave out on him, and he died on February 7, 2017. Obituaries and tributes were published in papers including the New York Times and the Telegraph. His remains are interred along with Blanche’s at Evergreen Cemetery just around the corner from his Tannersville home.

See more photos of Raymond in our gallery.